Ancestor Photos: Mysteries of the early portrait photographs in our homes

You might know a photo a lot like the one above, ancestors boldly meeting your gaze from out of the distant past, through a bubble of thick sturdy glass framed in heavy wood (or something like wood). An invitation to find

But, how did these

Photography came to Territorial New Mexico relatively early for such a young art. By the 1850’s itinerant photographers could be found plying their trade. Part artist, part alchemist, part travelling salesmen, these early daguerreotypists, tintypists and ambrotypists would travel from village to village, a mule loaded with equipment, pitching a tent or renting a shack where they might practice their craft for a few days or a week, sometimes timing visits to coincide with fiestas and other events that might bring families to the plaza. These early and often dangerous photographic technologies produced only one photograph for each exposure, making each image unique, teased out of chemicals and metal or glass, in the photographer’s makeshift studio. Sold to their subjects before the photographer left for the next town.

By the 1860’s, a new kind of technology changed the art of photography forever. Now photos could be reproduced from a negative onto paper, and this changed the business model for some travelling photographers. Now, photographers could send images away to be developed and reproduced, some as far away as early centers of the photographic industry, like Wabash Avenue in Chicago, home of the Bunch Portrait Company and the Chicago Portrait Company, whose promotional tags you might very well find on the back of your family portrait.

There was money to be made in upselling customers. A 10-cent photograph might become a $10 photograph when enlarged, enhanced and mounted inside those beautiful glass and wood frames. Often, photographers were partnered with a mail-order department store that might give you a framed copy of your photo, in the hopes that you would order more for your friends and family.

At those prices, photographs were a luxury item and their subjects took them very seriously. Photographs were no longer a novelty but portraiture on par with sitting for a painter. Formal dress and a serious demeanor dominate these images.

Later in the 19th Century, itinerant photographers faced competition from studio photographers in some of the larger territorial cities, but this didn’t really impact the itinerant photographers that served the villages of northern New Mexico, although one photographer, J.L. Smith, did set up shop in Questa in 1897 and 1898.

These photos were intended to survive the ages and it seems that many of them did, passed down from generation to generation, giving us a glimpse into the innate character of our ancestors.

Knowing what kind of early photograph you have, can be helpful in dating your ancestor portrait:

Daguerreotype – An image rendered in silver onto a copper plate, a daguerreotype will be reflective like a mirror and look somewhat ghostly and three dimensional. Your daguerreotype will likely date from 1845 to no later than the mid-1860s.

Ambrotype – An ambrotype will be an image fixed onto a glass plate, it will look like a negative until placed against a dark background, so your ambrotype will likely be mounted in a frame against a piece of black card or fabric covered board. Your ambrotype will date from the mid-1850s until no later than the mid 1860s. Ambrotypes, like daguerreotypes often came packaged in albums, in the case of an ambrotype the album would be designed to hold the ambrotype fast against the dark background and protect the fragile glass, however your ambrotype might just as easily lost its frame, and be mistaken for a glass plate negative, produced with essentially the same chemical process.

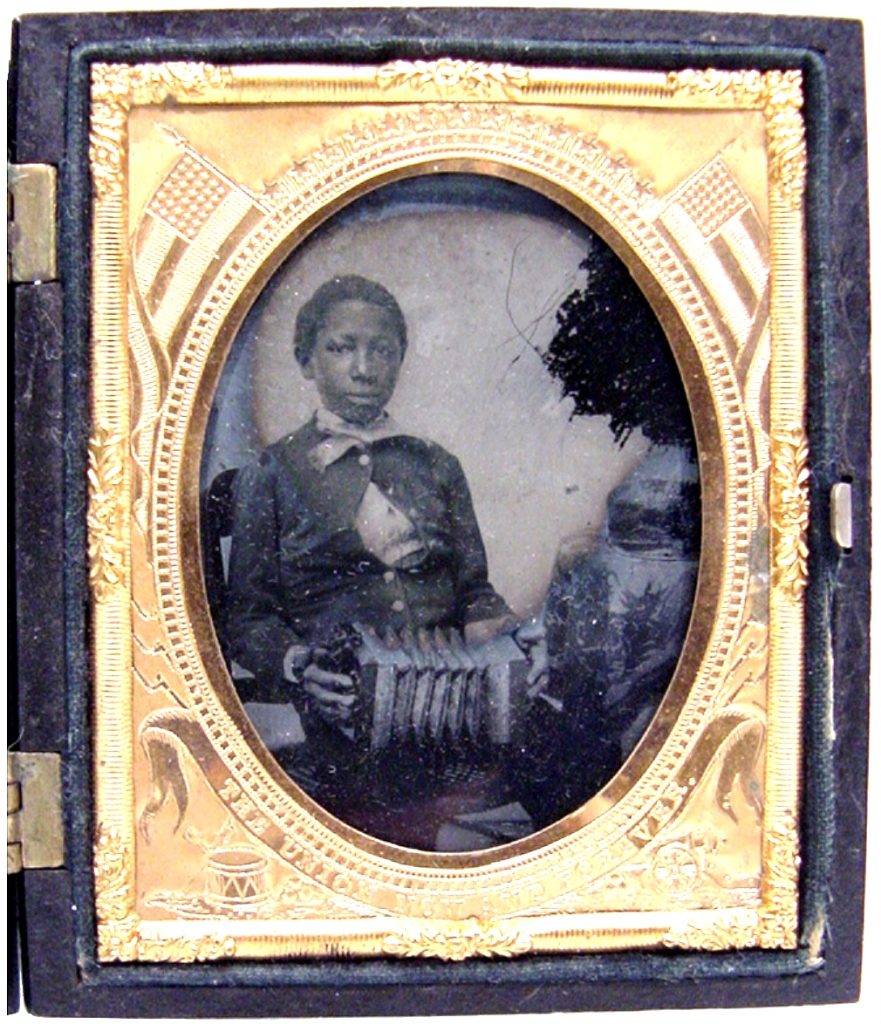

Tintype – The most common type of itinerant photograph. Tintypes were cheaper sturdier versions of the daguerreotype, fixed on a thin sheet of iron (not tin, despite the name) instead of copper. Tintypes appeared in the mid-1850s and persisted well into the 1930s. Although tintypes do not produce a negative, it is not unusual to have near identical tintypes. Some tintype cameras had multiple lenses, thus producing as many as 16 images from an exposure. As in the example below, your tintype might be collaged into a momento by the photographer or by a creative ancestor.

Albumen process – This is the technology that allowed for the industrialization of the photograph that produced the bubble glass and wood frame photographs. Generally, these photos are fixed to a thin film of egg-white based emulsion on paper or cardboard, before being mounted into frames, sometimes enhanced with color or foil. Your photo could date from as early as mid-1850s and as late as 1940, when newer photographic processes democratized photography and made this business model obsolete.

Please note that the first three types of photo are extremely fragile and the image can easily be destroyed with casual contact. Consider this when contemplating any handling of your photo. Albumen process prints are also fragile and in the case of bubble glass photos were often custom shaped to fit the curve of the glass and the frame, removing them risks severely damaging your photo. More on handling antique photos in later posts.

5 thoughts on “Ancestor Photos: Mysteries of the early portrait photographs in our homes”

Looking forward to seeing and learning more. Thank you.

Very interesting article. I have a few of these type images and have wondered about their time frame and the process. My family ancestors seemed to take many portraits at the Aultman Studio in Trinidad, CO.

I have a pitcher that just appeared in my house about 25 years ago it says Chicago portrait 7.98 with bubble glass I would like to know more

Great read and information! I have been blessed with several older photos and I’ve never thought to educate myself on the type and history surrounding the actual photograph/ photography.