Reflections of Africa in New Mexico

Every village has a remarkable story and Las Trampas, named for the River of Traps that flows through it, is no different. This village in northern New Mexico was settled in 1751 and holds the legacy of the remarkable families that gathered ground, tilled it and through the centuries made community. These families had come from Santa Fe, but at least one of their progenitors had himself carried an older origin story, one that reflected a journey of thousands of miles from Angola, revealing that a part of the story of New Mexico is buried in the layers of complexity and consciousness, unknown perhaps, but still there.

The representations of people of this place we now call New Mexico are often reduced to an early 20th century invention of three typologies — Anglo, Indian and Spanish — an enduring and yet deeply flawed mythology that continues to conflate distinctions between sovereign tribes and obscure the reality of centuries of mixture, born from acts of both love and violence. This myth also functions to erase entire groups of people from our history, including the presence and contributions of African origin people.

In 1812, Pedro Pino, an influential citizen was elected to represent New Mexico in the Spanish Cortes in Cadiz, Spain. In describing the conditions of the land and its people, like so many that would follow, he emphasized the purity of blood among New Mexicans, arguing that there was no known caste of people of African origin. “My province,” he declared, “is probably the only one in Spanish America that enjoys this distinction. Spaniards and pure-blooded Indians (who are hardly different from us) make up the total population of 40,000 inhabitants.”(1)

This must have seemed a ludicrous claim for those in earshot or those that would read his account, since the presence of Africans in the Americas was well known to all delegates. The first of those had arrived as early as 1519 with Hernando Cortés as enslaved peoples, a trajectory and experience that continued to flow into ports like Vera Cruz and radiate out and into every village in the Americas. New Mexico was no exception to this rule and even as early as 1598, the registries of colonists that joined Juan de Oñate in 1598 reveal a much more complex racial picture of settlement that most have acknowledged. (2)

Pino’s assertion that there were no known castes reflective of African presence was simply not true. According to many historians, by the mid 17th century, the African origin people comprised a significant number of New Mexico settlers. In 1661 Fray Alonzo de Posado, prelate of missions and Commissary of the Holy Office for New Mexico, described the province: “this land . . . does not have more than a hundred citizens, and among this number are Mulattos and Mestizos, all who have Spanish blood, even though it is slight.”Records of the era, include mention of household slaves, both “Indio” and “Negro” as well as many other mixed castes.(3)

Following the Pueblo Revolt in 1680, the resettlement included a caravan, that consisted of over eight hundred persons, including twenty-seven Negro and Mestizo families recruited in Zacatecas, Sombrerete, and Fresnillo. (4)

Among the settlers of the 1692 expedition was a man by the name of Sebastian Rodríguez Brito.

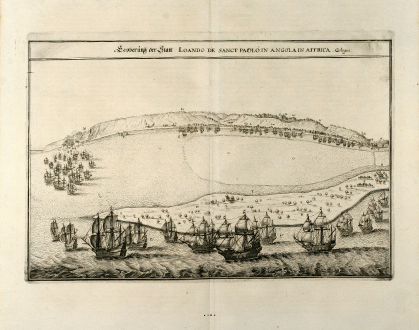

According to a record from 1689, Sebastian was born about 1642 to a Mbundu community in south central Africa and classified in a 17th century record as “de natión angola.” (5) Between 1580 and 1645, “Angolas” figured largely among the enslaved African populations of Spain’s viceroyal capitals in Peru and Mexico, and perhaps in Virginia.

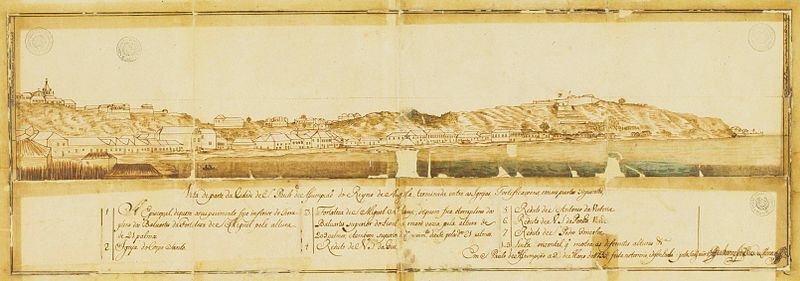

In another matrimonial investigation, Rodriguez indicated that he was fifty years old, and had been a resident of El Paso for seven years as the official drummer of the garrison. He noted that he was a native of São Paulo de Luanda, which at the time was under Portuguese domination and has since been recognized as one of the most important centers of the Trans-Atlantic slave trade. (6)

Based on the testimony provided in these records, Rodriguez was probably married before his residence in El Paso, though records from New Mexico reflect a marriage first to Isabel Olguín. Following the death of Olguín, Rodriguez succeeds in marrying a coyota, Juana de la Cruz, of unknown parentage, native of the Salinas district of New Mexico. In this record, he is identified as the son of Manuel Rodríguez and Maria Fernández, both “negros bosales,” a derogatory colonial term implying wild and uncivilized and generally referring to captured Africans.

From these early records we know that Rodriguez was the slave of New Mexico’s Governor Pedro Reneros de Posada by 1689 and perhaps later sold to Governor Diego de Vargas and later still to Governor Cubero. In his capacity as an enslaved individual, Rodriguez served as the official drummer and town crier of the garrisons in both El Paso del Norte and later in Santa Fe. Serving as the official drummer in the Santa Fe garrison was subsequently passed onto his son Esteban.

As a member of what Ira Berlin has called the “charter generation” of African slaves, which carried a certain level of social mobility, in time Rodriguez was able to both marry and acquire property. He was able to purchase property in Santa Fe in 1697 and sell land, as he did in 1706.

There is much more to the biography of Sebastian, including his wife being accused in a witch trial and his sons being granted land to settle what would become the Trampas Land Grant.

Building an archive demands the work of recovering the lives of our ancestors and the life of Sebastian Rodriguez is one worth remembering. For this place of places, Las Trampas has roots that extend 9000 miles into Luanda. It is a reflection of the beauty of Africa, just as those of us that descend from Sebastian are a reflection of him.

Notes

- Martha Menchaca, Recovering History Constructing Race: The Indian, Black and White Roots of Mexican Americans. University of Texas Press: Austin, 2001, pp. 81-88.

- Pedro Bautista Pino, Exposición sucinta y sencilla de la provincia de Nuevo México (Cádiz, 1812), 48 pp. The Pino Exposición has been called, “the most interesting and informative” of the informes made to the Cortes of Cádiz. See Juan de Contreras, Marqués de Lozoya [Professor at the University of Valencia], El informe del diputado par Nuevo México ante las cartes de Cádiz (Madrid: 1927) 36-48. Pino’s views on New Mexico are translated in H. Bailey Carroll and J. Villasana Haggard (eds.), Three New Mexico Chronicles: The “Exposición” of Don Pedro Bautista Pino, 1812; the “Ojeada” of Lie. Antonio Barreiro, 1832; and the additions by Don José Agustín de Escudero, 1849 (Chicago, 1942), p. 33.

- France V. Scholes, Troublous Times in New Mexico, 1569-1670 (Albuquerque, 1942), p. 6.

- J. Manuel Espinosa, Crusaders of the Rio Grande (Chicago, 1942), p. 129.

- Archdiocese of Santa Fe: Informaciones Matrimoniales, 1689, No. 1

- Archdiocese of Santa Fe: Informaciones Matrimoniales, 1692, No. 1.

5 thoughts on “Reflections of Africa in New Mexico”

Fascinating! There is much to say about our complex cultural and historical make up in New Mexico. Our African history begins in 1539 with Estebanico the Moor representing Spain at Zuni. Bravo!

Absolutely riveting, so much to learn about the people coming across the seas to settled the land and the people already living full lives when they arrived. The melding of so much culture, language and rituals is fascinating to me!!! Many thanks for sharing this history.

For those of us “Pure Bred” “Blue Bloods”, reality is not often kind, or maybe we are stubborn to recognize reality, in some cases based on science.

An individual of one of my family lines recently had some DNA work done. That primo/a was a Blue Blood Estremaduro/Estramadurense Español, until the results came in but now he claims dementia on this topic.

Now, my prim represents Norwegian, Nigerian, English, Basque, Middle Eastern,Italian, North African, Portuguese, Haitian, Cuban, but not a speck of the Jewish ethnicity. Then of course there is the Spanish, Mexican Indigenous, and Northern NM Indigenous components.

I don’t aspire to be a “Born Again” Christian, “Born Again” Jew (Crypto, Sephardic, etc.), “Born Again” Chicano, “Born Again” Indigenous Person. Mostly, I am just happy to be me. Soy quien soy.

Like my own Abuelitos, I remain a “Blue-Blood” Nuevo Mexicano Norteño. My prim must have been adopted, pobrecito.

Come on Dr. Martinez,

Your “emphasis on Blue Bloods”and Nortenos claiming to be pure Spanish , I have found and observed over the years comes from persons in academia!

Your average Nortenio is not obsessed with this notion of purity of blood. It is my observation that your down to earth Norteños are more concerned with putting 3 square meals on their respective tables to feed their families.

I have worked people at the university level and cleaning acequias with many of my blue collar gente and they are not obsessed with what runs thru their veins!

My 94 year old father with an 11 th grade education told me many years ago that we were a mixture of many cultures an people of color including blacks and I was present when he let the granddaughter of plantation owners know this after she commented on how Spanish he looked.

You know from your studies that anglos planted this seed of purity in our people when trying to gain statehood.

Some of my gente that do emphasize their Spanish roots do decend from Spanish families that came with the reconquest, and many have been very involved and close to the Catholic Church for generations. (Example: La Cofradia de La Conquistadora). I have ancestors that were mayordomos of that Cofradia. The statue and its orgins are Spanish.

The recently deceased Dr.Adrian Bustamante concluded an article he once wrote with a quote from an elderly norteña who when asked what we are she responded “we are what we feel in our souls”.

So come on brother cut your gente some slack and not be so hard on your people.

We have survived many obstacles over the centuries and survived. We need to educate our people but do it in a way that does not affect their pride and self esteem.