Digital Cuaderno Special – ‘The Strength of Cerro’ by Douglas Paul Cordova (1984)

Not long after the COVID-19 Pandemic started to sweep across the United States, early this year, The Manitos Project responded by initiating the ‘COVID-19 Digital Cuaderno’. Understanding that although everyone would have a pandemic story to tell, we wanted to make sure that Manitos voices and experiences were documented and heard amidst the sudden flurry of COVID documentation.

As the project came together, we here at Manitos Project mission control, being the history nerds that we are, couldn’t help but recognize that New Mexico had survived a unique set of experiences during the 1918 ‘Spanish’ Influenza Epidemic, as well.

New Mexico was a relatively new state, without an established health department and in many ways, Manitos country was still ‘off the grid’ when it came to infrastructure. If there was anything resembling a comprehensive response to a national health crisis, the mountain villages of Northern New Mexico and Southern Colorado would not exactly be on its map. In 1918, Manitos were still very much on their own, in so many ways.

We decided to collect stories about the 1918 Epidemic to sit alongside COVID stories and as we started to reach out, one of those things that history nerds live for, happened. An unexpected surprise beyond one’s wildest expectations.

Mr. Doug Cordova, in correspondence with Manitos Project director, Dr. Estevan Rael-Galvez, revealed that he had something quite interesting; a college essay that he had written, based on an interview conducted in 1984 with his tía, Claudina Martinez Sanchez, in which she spoke at length about her life in Cerro, New Mexico.

Although she only briefly mentions the epidemic itself, what Tía Cluadina revealed, as she sat at her kitchen table, telling her story to her college age sobrino taking it all down pen to paper, is a rich and rare portrait of a Manito world that the 1918 Epidemic disordered so mercilessly.

It is worth mentioning that Mr. Cordova, a mere 20 years old, when he conducted this interview in 1984, had been a genealogy enthusiast and family historian since the age of 14. This interview which sat undisturbed in his records since he turned it in for a grade almost 40 years ago, is a rare oral history, collected from a generation that had for the most part passed by the time documenting this kind of intimate family history had become a more common practice. Mr. Cordova’s youthful avocation, allowed him to capture this portrait of his tía, while her memories were still vivid.

Mr Cordova speaking recently about his Tía Claudina, had this to say:

“Visiting Tia Claudina was always a special time for me. While I grew up in Albuquerque, most of my Father’s extended family lived in Colorado, so we routinely traveled through Cerro on the way to our visits up north. On these trips, we always stopped to see Tia Claudina and Uncle Ben. Every time I saw her was an emotional experience. She would greet us at the door, tear up, and say to me, “Mi Hermano Jose,” as I reminded her of my Grandfather. I do not know if inspirational is the right word…moments like that are hard to capture in words, but, maybe, overpowering paints a more accurate picture. So warm and full of life and love, you never had to wonder what Tia Claudina was feeling or what was she was thinking. Those heart-felt greetings are forever emblazoned in my memory to this day, bringing a smile whenever I think of her.

It is examples like that small snippet in time which highlight Tia Claudina’s spirit and became the catalyst for the title of my paper detailing some of her life’s stories. Her resilience, determination, and love of family embodied the true Strength of Cerro. It symbolizes the people who lived there and made a difference for their families and their community on a daily basis against the constant backdrop of the trials and turbulence of inclement weather, death, and the separation of family as many of her men were forced to travel north for seasonal work. This left a people reliant on one another as they woke each morning and resourcefully used whatever they could to tend to their homes, work the land and livestock, and build their lives. Those who lived there possessed an inner strength to battle the odds and make the most of life. This is what I think about when I visit my relatives there and those buried across from the Morada…this is what I think about when I think of Tia Claudina.Tia Claudina embodied a loving, enduring spirit. A proud legacy of survival and family tradition, tempered and shaped by the past. I felt it each time I sat down with her. Now, I readily admit my Spanish is not very good and English was not Tia Claudina’s first language. And, while she did speak English fairly well, it really didn’t matter because we the communicated on a different level only understood by those fortunate enough to share a piece of our culture, one created by just being together and celebrating our connection. Although I have to tell you, we would usually get some stew with mutton during our visits which was like chewing on a piece of rubber. I did not enjoy that special treat, but chewy mutton was always completely overshadowed by the time spent with the Strength of Cerro…and a few homemade tortillas!”

So, as a tribute to Mr. Cordova’s foresightedness as a young documentarian and to his tía who so patiently and vividly gifted her sobrino with her memories, we present Mr. Cordova’s extraordinary document in its entirety as it was written on a ribbon typewriter in 1984, with only the slightest edits for clarity.

The Strength of Cerro

by

Douglas Paul Cordova

History 261

1-21-84

This is the story of Claudina Martinez Sanchez, whose strength and character are matched by none. Claudina’s father, Donaciano Martinez, was born in Cerro, New Mexico, in 1867. Her mother was Celestina Arellano, and she was born in Costilla, New Mexico, in the year 1876. They were married in 1892 and lived in Cerro.

Donaciano’s father Nestor owned 48 acres of land in Cerro and divided this between Donaciano and one of his brothers, each receiving an equal 24 acres. On this land Donaciano would grow his crops and raise his livestock. During the months of April through October, Donaciano, like other men in Cerro, would travel to Wyoming and other surrounding areas to become sheepherders. During this time Celestina would be left alone in Cerro; this could be the reason why two of Celestina brothers were living with the Donaciano family in the 1900 Territorial Census.

Death had a common place among the people who lived in this time. In 1900 Donaciano and his brother Eulogio were the only children left of the 11 children his mother gave birth to. Celestina had 12 children of whom only 7 were living in the year 1910. Even Donaciano and Celestina could not escape the treacherous toll of infant deaths. Celestina’s first five children died as babies. Claudina was born November 12, 1915, the twelfth child born to Celestina. Only three years later, in 1918, Claudina’s father was swept under by an influenza epidemic.

Claudina’s brother Philemon died in 1919 at the age of 17, and her newborn sister Rumaldita died that same year, possible victims of the same epidemic that claimed their father. The people who died of this sickness were buried fast for fear of contamination of others.

This left Celestina the job of running the household all by herself. By the time of Donaciano’s death, the two oldest girls, Patrocina and Refugio, were married. One of Celestina’s children, Filigonio, lived in Costilla with his grandparents. This left three children at home, Antonio Jose 12, Pasqual 5, and Claudina 3.

Celestina had to be both mother and father to these children. Claudina described her mother as a hard worker who set good examples. Celestina loved her children very much, and that love was felt by her children. She sacrificed a lot for her children and, because no assistance was available, all she had was the land to make it work. Some mornings Celestina would get up, pin up her dress since she had no pants, put on irrigation boots and help her brother Antonio Avan irrigate the fields. During times of the year when Antonio Avan would leave to herd sheep, Celestina was left by herself for months.

On their land they grew wheat, corn, beets, and squash. Their livestock consisted of 10-15 goats, 15-20 sheep, 6 pigs, and around 25 chickens. The only items that needed to be bought were sugar, salt, coffee, and bolts of cloth to make clothing. The eggs received from their chickens were not consumed by the family, but rather used as barter at the grocery store for the needed items.

Animals were sold in order to buy shoes and cloth for clothing. The girl’s undergarments were made from flour sacks. They resembled today’s bloomers extending down to the knees. The boys received store bought underwear. Flour was obtained by taking the wheat from harvest to the flour mill in San Luis and having it ground.

Claudina’s duties consisted of pulling weeds to feed the pig three times a day and doing a variety of household chores. Around the age of six, duties included things like doing the dishes. By the age of ten, washing the floors and cleaning the house were done. Another big task was the cleaning and mending of the mantas. This was the cloth ceiling made out of linen sewn together. It was nailed to the wall all around the room. Twice a year the mantas were taken down, sewn, and thoroughly washed by hand before being tacked back up.

Above the mantas were the vigas, which are open beams, and between these beams latias, which are small chips of wood or bark. Dirt was spread across the vigas and latias and packed. The purpose of the latias is to stop the dirt mud from falling through onto the mantas.

When it would snow, the girls would have to get up on the roof of the home and sweep the snow off. If it were allowed to melt, mud would seep through to the mantas. If the mantas were to get dirty, they would have to be taken down and cleaned.

The inside of the house was considered woman’s work and many outside chores were considered man’s work. This division of labor was not always recognized by the fact that many times the woman would be left to make the decisions and take care of the household by herself.

The sweeping of the patio was one outdoor job that women did. There was a saying that one could tell about the people who lived in a house by how clean their patio was. The patios were made much in the same way as the roofs on adobe houses were made. When the patio was cleaned, it was cleaned clear back to the corral, and it had to be spotless.

Another chore majorly done by women was the plastering of adobe houses. This was usually a community affair. They would start at one side of the town and work across to the other side of the town. Certain people were responsible for feeding them.

Celestina’s oldest girl Patrocina died in 1930 of pneumonia and other complications soon after giving birth to her second child. This left Celestina with two more children to care for, Elsie and Rosita.

Because no doctors were in the area, many people died of illnesses considered today to be minimal such as a cold or the flu. The major types of sickness were cold, diphtheria, smallpox and the measles. The only available ways to cure these sicknesses were home remedies. These consisted mostly of plants and herbs. Gray Sage Brush was considered good for colds because it possessed large quantities of quinine. It was used to bathe in, used as a vaporizer, and drunk in tea. Chamisa was considered a good cure for stomach problems. The medicine used depended on the symptoms a person had. If someone was experiencing high fever, sliced potatoes would be soaked in vinegar and baking soda stuck on the forehead and wrapped. Serious injuries were taken to town if the individual lived that long.

A death in town was sounded by Doblaban, which was three raps on the church bell. This was distinguished from the ring for church services by three distinct raps as opposed to constant ringing. Usually the people knew who had died because they knew who was sick. If it was a sudden death, news was transferred by word of mouth. Upon hearing of a death, people would come to the house of the deceased. The family members would bathe and dress the member of the family who had died.

Then the body was placed on a type of scaffold. This scaffold was the same used by everyone else in the town. The body was placed in the living room and a rosary was said that evening. Then the family and friends would sing and pray all night long. People would mind the kitchen, and those who remained would be fed at midnight. This gathering was culminated at dawn with the singing of la lava [note: could he mean alabados?]. A mass followed later in the day, and they were buried.

The life of the people in Cerro was surrounded with tragedy and work, with very little time for recreation. This may explain why they tied themselves so closely to religion. It gave these people a reason for pushing on and it was an answer to so many questions they had.

In Claudina’s home the rosary was said every night. Religion was the basis for everything. All the holidays they celebrated centered around the belief in God and their religion. There was the Feast of Our Lady of Guadalupe, who was the patron saint of Cerro (Cerro Guadalupe). There was the Feast of San Antonio in June, and the Feast of Santiago and Santana, which was celebrated with a large festival in Taos. On the Feast of San Juan de Baptista, it was traditional for people to take a bath in the ditch. On the Feast of San Isidro Labrador, a statue of Saint Isidore, who is the patron saint of the laborer, was carried in a procession across the field for a good harvest. At the end of the procession everyone would go to a person’s house for a feast.

Christmas was a celebrated time of year. Gifts were not received from parents or between brothers and sisters. Instead it was much like present day Halloween. Children would go from house to house in trick or treat style. Candy and fruit were big things, especially oranges, which were not as abundant. Occasionally money was received.

A big event at Christmas time was Las Posadas, or the re-enactment of Joseph and Mary’s search for a room in the inn. Posadas would start nine nights before Christmas. Those involved would go to each house asking for a room. Then they would sing and pray. Another Christmas festivity was Los Pastores. This was a play of shepherds who followed the star to Bethlehem. It consisted of seven pastores (herders), one girl, believed to be a daughter of a shepherd, and a devil which tempts the lazy shepherd not to go and see the child in the manger.

New Years was also celebrated. The coming of the new year was welcomed on its eve by a dance which lasted until midnight. At dawn the following morning, people would go to each other’s houses and sing the mananitas. These were songs with words you and the person singing with you made up and incorporated into the song. Then you were invited into the home and given a shot of whiskey or something similar.

By far the biggest religious celebration was Holy Week. In Cerro, there were the Penitentes, which is a brotherhood of men. Women can be auxiliary members. Many controversies surround the Penitentes. It is believed that 200 years ago actual crucifixions took place. Violent flagellation does not exist anymore to my knowledge, but at one time it was used to emulate the suffering of Christ and as a form of penance. Today in Cerro, Holy Week with the Penitentes begins with skits and the praying of the rosary every night.

At the end of the week, El Encuentro is performed, which is a play of the crucifixion. At one point in the play, Jesus’ face is wiped by a woman and his image remains on the cloth. Claudina’s brother Pasqual, who was a gifted artist, drew this image. It is not known if this same cloth is used today. The week ends with the tinieblas. This is basically a ceremony in the morada or the church.

Although most of the community’s social activity revolved around their religion, some did not. Claudina first met her husband Ben Sanchez at a dance. Dances were held for special occasions such as weddings and other festive events. They took place at someone’s house since no dance hall or building was available. The furniture in the living room of the home would be taken out and chairs placed at the outer perimeter of the room. The music played was basically violin, guitar, or accordions. These dances usually ended at midnight, and an older man with his lantern roamed around to make sure that everyone went home.

Children of this time were seen and not heard. They were taught to have the utmost respect for their elders. The age of adulthood was considered 17 or 18, much like today. The community of Cerro had a population of around 800 people in 1930, so everyone knew everyone else. The community was very tight-knit. If an animal was killed, everyone in town receive a portion. The immediate family was very close. Very few disputes broke out because they needed each other. Claudina recalled the time she moved her brother’s room around and when he returned it was dark. Before going to bed he knelt down to pray, but no bed was there, and he fell flat on his face. He was sure mad the next day.

The extended families were also very close-knit. Celestina had many relatives that lived in Costilla, New Mexico, and trips to see them were made about once every two weeks. They traveled by horse and buggy and would leave around 1 pm, only to return the next day.

The government of Cerro consisted of elders usually nominated by the people. These men were considered the jefes and turned to for guidance. They operated like a city council, and punishment was usually in the form of some type of fine.

Priests were also very influential in Cerro due to the religious faction that existed. With the new United States Government, there was a great ignorance of the law and not much known of the government. For this reason, many people weren’t aware of the appeal process and lost much of their land to the Forestry Service.

One good aspect of the new government was in respect to education in schools, but even this was severely limited. In the vicinity of Cerro, there were three different schools. Two of them were two-room, the third had only one-room. The number of students in the school ranged from 15 to 20. Everyone used the same classrooms, so different grades would come in at different times of the day. They would be taught for a while and then sent home. Claudina attended school all the way through eighth grade.

Further education was very hard to obtain. A high school didn’t open up in Questa until 1930, but this was still five miles away. Claudina’s husband Ben traveled to Albuquerque to attend Menaul High School. He had to withdraw from Menaul because his parish priest told his father he would excommunicate him if Ben was left in that Presbyterian school. So Ben came back and took out a room in Taos to go to high school.

Ben Sanchez and Claudina Martinez were married in 1938 and their first son was born in 1940. They would have two more children, Gene and Carolina. Before Celestina passed away, the land in Cerro was transferred to her son Pasqual. This was because he was a veteran, and he didn’t have to pay any property tax. Ben and Claudina purchased the land from Pasqual and still own the 24 acres today.

They also own land up in the mountains near Cerro. Ben’s father and uncles had homesteaded there and started the Midnight Ranch in Red River. After Ben’s dad passed on, the land was split between Ben and his brothers. As was stated before, over half this land was taken by the U.S. government for the Forestry Service.

The house which Ben and Claudina live in now is located between Questa and Cerro on Highway ?3. The house in which Claudina grew up was torn down and the adobe blocks were used as insulation for their new home.

Most of the people when Claudina was growing up were Spanish, and that was the only language spoken. There were very few French and Anglos in the area. Indians were no longer a problem because the Utes had already moved to Colorado. The only other Indians around, if they were not already incorporated in the culture, were found in Taos at the pueblo. Therefore, there was really no prejudice; everyone knew each other and go± along. The only people they tried to stay away from where those thought to be brujas or witches. One case involved Claudina’s brother Antonio Jose. He was carrying a load of wood home when a lady who thought he looked thirsty offered him some of her mula or home brew. Soon after this Antonio began to have stomach problems and it was believed that the woman put a hex on him. From that point on, Claudina’s family tried to ignore her.

Unlike most Spanish people, Claudina is not very superstitious. She does however believe that before someone close to you dies, family or friend, they may come and say good-bye. This can be done in a variety of ways, but mostly by odd occurrences prior to their death.

Claudina has mentioned how much work was a part of her life. She splits it up to about 90% work and only 10% recreation. As a child she remembers playing dolls with two sisters across the road. When she got older, they would ride burros or one of their two horses, La Mora or Jack. The people of this time were very imaginative and very creative. Much time was spent eating pinons and listening to the riddles and stories of the elders. Stories were told of the past and sometimes of the brujas.

The way Claudina was raised affected greatly the way she raised her own children. Much love, prayer, and discipline were needed in their lives. Everyday Claudina’s children would say the rosary, and religion was made a big part of their lives, as it was hers.

Celestina, Claudina’s mother, thought the television was a tool of the devil. Although Claudina watches it every once in a while, she believes youth today is paying too much attention to it. A big problem today, she says, is the lack of discipline, and a good example of this concerns drinking. Claudina is a firm prohibitionist. Many of her beliefs reflect her firm upbringing. She is strong in what she believes in, and she is not afraid to share her beliefs. Although she has these strong beliefs, she does not try to force them upon you. As she learned, she teaches by example.

This paper is written about a lady, my great aunt, who cannot be described by simple words. The most important thing in her life is her family. When her brother Pasqual died, the flag of the United States was draped over the coffin because he was a World War II veteran.

Pasqual’s son-in-law, a veteran of Vietnam and a Jehovah’s Witness, is bitter toward the government. Because of his religion, he doesn’t believe in symbols like the flag. Upon seeing the flag on Pasqual’s coffin, he pulled it off and threw it on the floor. But Claudina was proud of her brother and proud of the flag. Today in her home she has a nice charcoal drawing of Pasqual. In the corner of the frame of this drawing is a picture of Pasqual’s daughter, her husband, and her child. Above this picture is a permanent sticker of the United States £lag. This is the type of person she is.

This paper is called The Strength of Cerro because those like Claudina are the strength of Cerro. Her strength, pride, and religion are what make her personality unmatched and emulated. You cannot help but be touched by it. A woman unafraid to show emotion, she would give everything she has to those she loves.

Claudina was brought up knowing hardship. Believing strongly in her religion provided comfort when life was hard, and this made her strong, and it made Cerro strong. Even though few people live in Cerro now, and many of the people in her life lie in the dirt cemetery across from the church, the strength and the pride of Cerro live on in Claudina and those who have the privilege of knowing her.

1. Campa, Arthur L., Hispanic Culture in the Southwest, Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1979, p. 209

2. Campa, p. 209

3. Campa, Arthur L., Hispanic Culture in the Southwest, Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1979

? Sanchez (Martinez), Claudina, p.c., 1984.

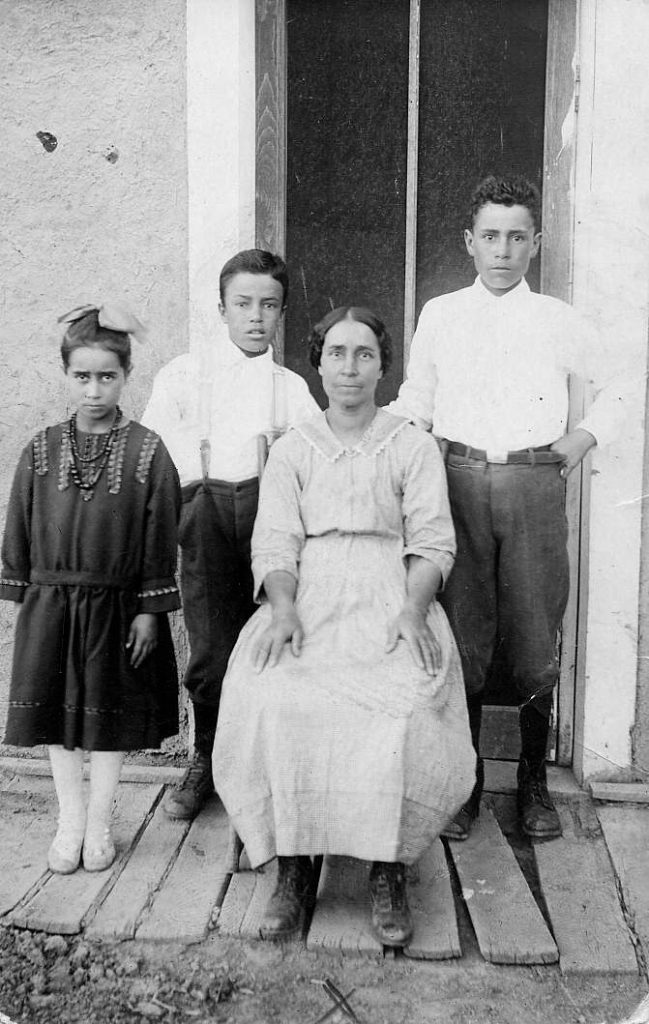

Featured Image: Claudina with her Grandfather, Antonio Domingo Arellano. (detail) (photographer unknown, courtesy of Doug Cordova)

2 thoughts on “Digital Cuaderno Special – ‘The Strength of Cerro’ by Douglas Paul Cordova (1984)”

Thank you! My father and other family members are sure to enjoy this story!

What an amazing account, of a courageous women. A beautiful tribute to her. The hardships endured by these people, is difficult to comprehend. Great job!